I'm working through the excellent Practical Deep Learning for Coders course, and one of the key traits of the course is the top-down approach to learning - practical application before theory.

In the spirit of that, I've decided to create a full end-to-end project that identifies the breed of birds in my backyard's bird feeder (part of my longer term goal of creating my own motion-sensing, annotated, images and videos of birds that visit).

As I worked through this project, I began to appreciate very acutely what I now call The Perils of Dataset Curation 😱.

Bird Identifier

In the course, Jeremy's suggestion is to work through an end-to-end project to really get a feel for deep learning in practice. I loved this idea, and I had the perfect project in mind - I wanted to know the various breeds of bird that visited my backyard's bird feeder.

Being the good student and wishing to avoid falling trap to the common problem of trying to annotate the perfect dataset as discussed in the course, I decided to limit the scope of my project significantly. There are an incredible amount of bird breeds around the world, and even just in North America, but I really only needed to know about the ones that related to my project - birds that frequent bird feeders in Florida.

To that end, I found a neat website that identified exactly those birds, Florida Backyard Feeder birds: The Definitive Guide. They have a super cool table of the top 30 birds by frequency of observation in backyard feeders. Right click as well as text selection was disabled on this site, so I wrote a quick script to scrape the data.

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import httpx

r = httpx.get("https://avianreport.com/florida-backyard-feeder-birds/")

soup = BeautifulSoup(r.text)

bird_rows = soup.select_one("table").find_all("tr")

birds = []

# The first column is the header

for row in bird_rows[1:]:

bird_cols = row.find_all('td')

birds.append(

{"bird_name": bird_cols[1].get_text(), "feeder_frequency": bird_cols[2].get_text()}

)Birds in hand (😏), I moved on to creating my dataset.

Downloading Many Bird Pictures

Understanding that you can't make any good neural networks without tons of data, it was time to download lots and lots of bird pictures! 🐦

There are many approaches that can be taken here, but I went with Bing's excellent image search API. While actually getting an API key from Azure is an endeavor so fraught with complexity it's comical (Really Microsoft?? Just give me the API key!! Look how simple OpenAI makes it! 😤), the API itself is quite nice.

import fastai.vision.all as fai_vision

import fastai.data.all as fai_data

sub_key = "BING_API_KEY"

search_url = "https://api.bing.microsoft.com/v7.0/images/search"

headers = {"Ocp-Apim-Subscription-Key" : sub_key}

params = {"license": "public", "imageType": "photo"}

urls_downloaded = []

for bird in birds:

bird_name = bird['bird_name']

bird_name_path = '_'.join([o.lower() for o in bird_name.split(' ')])

bird_res = httpx.get(

search_url, headers=headers,

params={"q": bird_name, **params}

)

bird_urls = [

o['contentUrl'] for o in bird_res.json()['value']

if o['contentUrl'] not in urls_downloaded

]

urls_downloaded += bird_urls

fai_vision.download_images(Path('./datasets')/'bird_id'/bird_name_path, urls=bird_urls)

sleep(2)The Bing API defaults to 35 images per search, so we should have about that many in each of our bird folders. Now it's time for the fun part - training our model!

Train the Model

First, lets get our data into dataloaders and have a look at what we've downloaded.

bird_id = fai_data.DataBlock(

blocks=(fai_vision.ImageBlock, fai_data.CategoryBlock),

get_items=fai_vision.get_image_files,

splitter=fai_data.RandomSplitter(valid_pct=0.2, seed=42),

get_y=fai_data.parent_label,

item_tfms=[fai_vision.Resize(224)]

)

dls = bird_id.dataloaders(Path("./datasets/bird_id/"))

dls.show_batch(max_n=8, nrows=2, figsize=(10,4))

Well, I'm definitely not a bird expert, but other than the mislabeled owl, that looks reasonable. Let's keep going and train a simple model on the current data.

learner = fai_vision.vision_learner(

dls, fai_vision.resnet18, metrics=fai_vision.accuracy

)

learner.fine_tune(5)My accuracy from this first run was 54%. Well, it's only our first attempt, but that's not great. It's possible that we don't have enough samples per class, or perhaps our data isn't very clean. But before we go any further, let's have a look at the confusion matrix to see if anything jumps out.

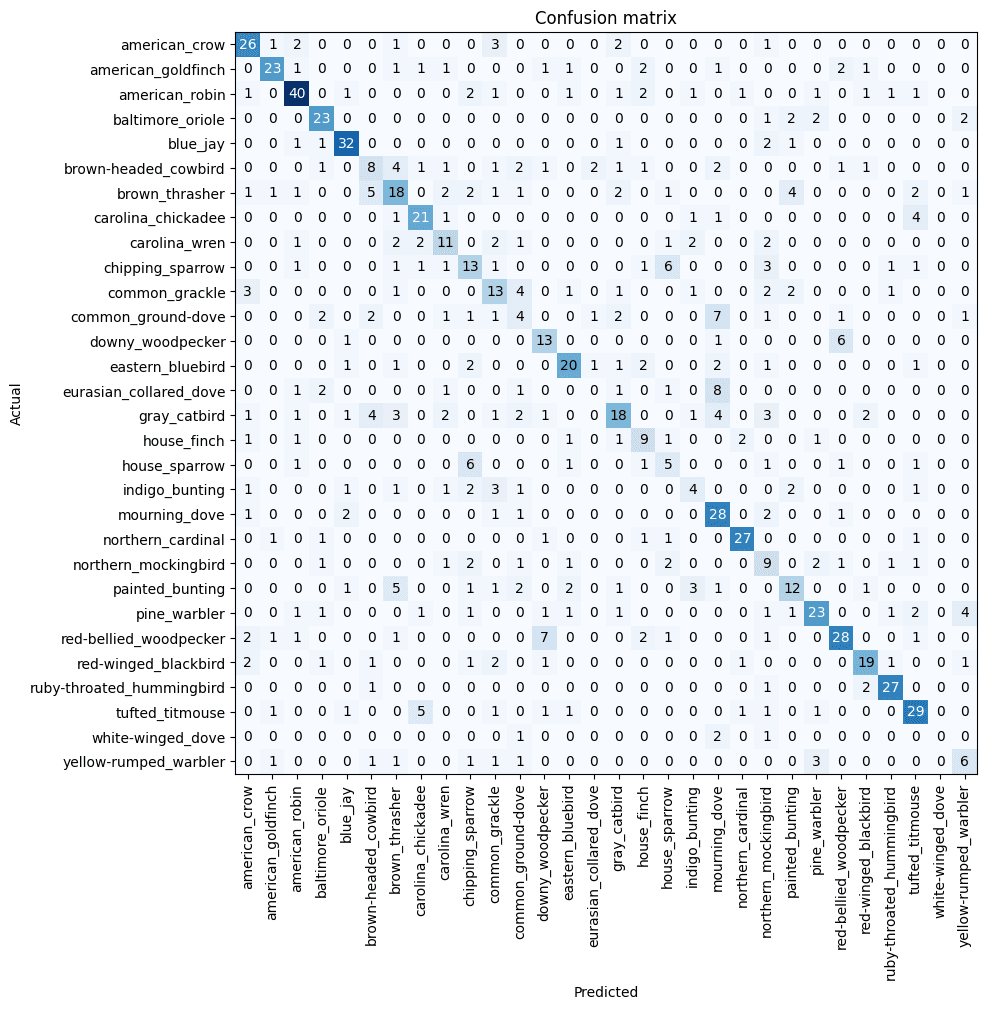

interp = fai_vision.ClassificationInterpretation.from_learner(learner)

interp.plot_confusion_matrix(figsize=(10,10))

Ok, so there are some things that are really clear from this confusion matrix. The birds that are very unique and stand out have a high accuracy - Northern Cardinals, Blue Jays, American Robins. However, our model is currently quite bad at predicting less distinctive birds, particularly those which have multiple subtypes. For example, there are several types of doves, all of which the model confuses between - Common Ground Dove, Eurasian Collared Dove, Mourning Dove, and White-winged Dove. Further, we appear to have too few samples for some of the particular subtypes - perhaps our search didn't yield good results for these birds.

So it's clear that at the very least, we don't have enough examples of some of the birds. I went ahead and repeated the data-gathering process to include searches for the bird's name, another search for bird_name shade and bird_name sun to get some different lighting varieties, and also bumped the images per search from the Bing API to 150.

I retrained the model and got 55% accuracy - barely an improvement. I tried the resnet50 architecture just in case 18 was too simple to capture the subtle differences, but I was only able to get to a max of 62% accuracy. So at this point, since we've barely improved after more than tripling our images, it's likely we have other issues. Let's have a look at our top losses at this point to see our worst data.

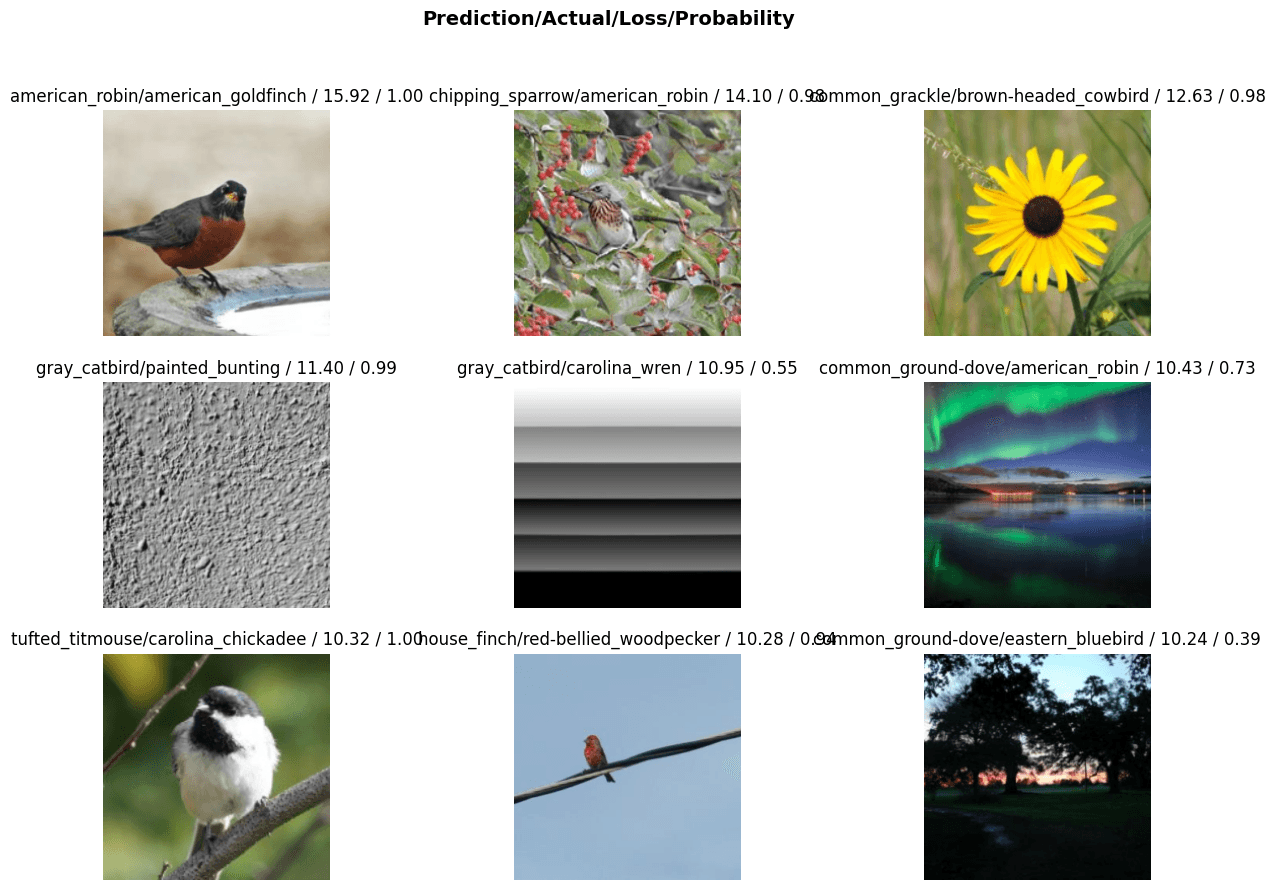

interp.plot_top_losses(15, nrows=3, figsize=(30, 10))

At this point things are starting to become pretty clear. There are a bunch of different issues in this small batch alone. We have blank images, images of auroras and sunsets, random objects, other animals completely (I saw a squirrel and a turtle in a few batches). Beyond that, there are also lots of images that are clearly going to be very poor additions for training our model - those that are almost entirely obscured by branches, chicks that have just been born, or large groups of birds that are at a distance.

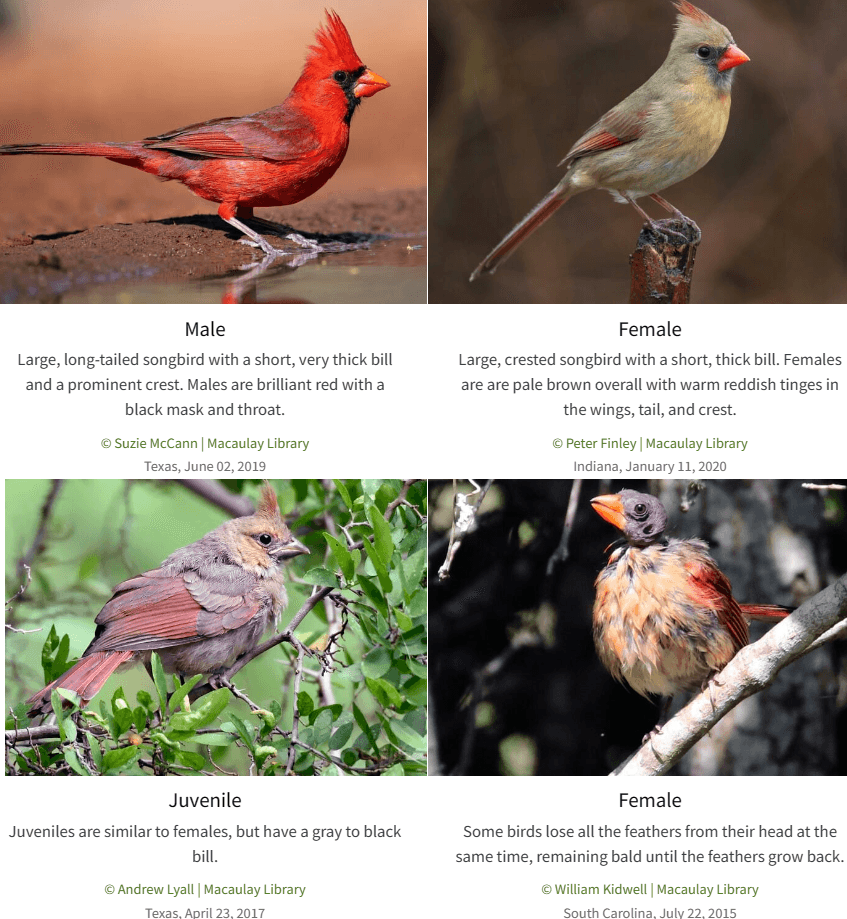

Since I'm not a bird expert, I did a bit of searching online during this process to identify some of the birds to check the labeling and I encountered another issue that turned out to be even more substantial. As it turns out, some bird species may look like completely different species to the untrained eye depending on their gender, breeding status, whether they are molting, and their age.

For example, have a look at this set of images of Northern Cardinals from All About Birds.

I knew some females weren't as distinctive as males, but I had no idea the juveniles and molting females look like completely different birds. How many different combinations of looks do just these 30 breeds have? Frankly, I'm surprised our model was even able to get above 50% accuracy on just these 30 breeds. It would probably take me many hours of arduous work to properly collect, clean, and label enough data to get reasonable accuracy.

After looking through some of the search results for a Northern Cardinal, it's also clear we have a bias built into our model already - the most distinctive form of each bird is most likely to show up (for example, the male cardinal almost exclusively appears in the top results), which makes sense - those are the most interesting birds to look at and take pictures of. Furthermore, there are many more good examples of birds with distinctive features and colorations in search results compared to more common birds such as doves.

Based on all this, our model would likely perform much worse in the real world, where males, females, and juveniles likely have similar distributions, but our model would only recognize the males accurately and consistently.

Stepping Back

I may have thought I was avoiding the trap of spending way too much time cleaning data and curating the perfect dataset by dramatically limiting the amount of bird breeds I was looking at, but clearly I'm still having this exact issue! However, I'm glad I encountered this in practice so early. I feel like just having a glimpse of the difficulty of putting together a seemingly simple labeled dataset will help me frame future problems a bit more realistically. It also certainly helps you appreciate the work that goes into curating these datasets that are made available publicly!

On that note, I found an excellent and extremely thorough North American birds dataset from The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, kindly made freely available for non-commercial use. There are 400 species and 48,000 annotated photos, over 100 per species, and separate annotations for males, females, and juveniles.

Using the New Dataset

This dataset contains both the images and some helper functions for processing the labels and classes. In the images folder, we have a folder for each bird class ID with images for that class. There is also a text file mapping class IDs to class (classes.txt), image ID to class (image_class_labels.txt), and image ID to image path (images.txt).

Continuing with the theme of keeping things simple, I wanted to use only the birds related to my project. classes.txt has the bird names, but also contains hierarchical class data (e.g. birds -> perching birds -> Chikadees and titmice -> oak titmouse). We want just the most specific bird information, so we can filter for that first, then map all our classes to their associated image paths and copy them over to our project folder. I converted the class IDs to class names to use as folder names for ease of use.

import os

import shutil

import nabirds

dataset_path = ""

image_path = "images"

# Parse label data using the provided nabirds functions

image_paths = nabirds.load_image_paths(dataset_path, path_prefix=image_path)

image_class_labels = nabirds.load_image_labels(dataset_path)

class_names = nabirds.load_class_names(dataset_path)

class_hierarchy = nabirds.load_hierarchy(dataset_path)

# Top level classes only (those with no child classes) are just the image folder names

# Strip leading zeroes from folder names to match classes.txt format

base_classes = [c.lstrip('0') for c in next(os.walk("./images"))[1]]

# Get the class names for our birds of interest, filtering for only the base class

# This subdivides birds with multiple distinct looks

# E.g. American Goldfinch

# -> American Goldfinch (Breeding Male), American Goldfinch (Female/Nonbreeding Male)

target_bird_list_subdivided = []

for bird in target_bird_list:

target_bird_list_subdivided += [

class_name for class_label, class_name in class_names.items()

if class_label in base_classes and bird in class_name

]

target_bird_list_subdivided = list(set(target_bird_list_subdivided))

# Map each of our bird classes to a list of image paths

bird_image_paths = {}

for bird in target_bird_list_subdivided:

target_bird_class_labels = [

class_label for class_label, class_name in class_names.items()

if bird in class_name

]

target_bird_image_ids = [

image_id for image_id, class_label in image_class_labels.items()

if class_label in target_bird_class_labels

]

bird_image_paths[bird] = [

image_path for image_id, image_path in image_paths.items()

if image_id in target_bird_image_ids

]Finally, we can move just the target birds from the full dataset to our training folders.

def clean_bird_name_path(bird_name: str) -> str:

bird_name_path = re.sub(r"[ \/]", "_", bird_name)

bird_name_path = re.sub(r"[A-Z]", lambda m: m.group(0).lower(), bird_name_path)

return bird_name_path

nabird_base_path = Path(r"./images/")

dest_base_path = Path("./datasets/bird_id")

for bird_name, paths in nabird_paths.items():

for path in paths:

orig_path = nabird_base_path/path

bird_name_path = clean_bird_name_path(bird_name)

dest_path = dest_base_path/bird_name_path

dest_path.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

shutil.copy2(orig_path, dest_path/orig_path.name)Now that we a nice, tidy dataset, we can retrain our model to see how we do.

A Great Model

I fine tuned resnet18 again for 5 epochs and achieved almost 80% accuracy with the new data, an improvement of almost 30% over even resnet50 using the dirty data, and without all the biases inherent to using images scraped from a web search!

Though 80% was substantially better, I was hoping to have higher accuracy when identifying my bird feeder birds, so I tried a few bigger models. resnet50 achieved 87% in 5 epochs, which was another good bump.

I wanted to see if I could get it higher, but I wanted to make sure inference time took less than around 1 second since my long term plan is to have a motion detection camera system which takes multiple images and segments all the birds for identification, which may happen multiple times a second. Using Jeremy's excellent Which image models are best? Kaggle notebook, I found convnext_tiny.in12k_ft_in1k_384, the best performing model with a 0.001 second inference time.

Fine tuning this model for 5 epochs yielded an accuracy of 94%. I think that will be plenty for my humble backyard bird feeder identifier!!

Time to test our model on some images outside of the curated dataset. I found a really nice picture of a northern cardinal online as a first test.

Prediction: northern_cardinal_(adult_male), Probability: 99.997%

Looks like our model is right, and almost 100% certain of it! Ok, but that's a beautiful professional photo of the ideal specimen. How will it do in the real world? I don't have my camera set up near my bird feeder yet, but I have snapped the occasional photo when I see birds at the feeder. Unfortunately, these are extremely low quality, 5x-optical-zoom camera phone pictures through my dirty window and even a window screen. But that should be a true test for our model, right?! 😬

Prediction: red-bellied_woodpecker, Probability: 99.912%

Right again! Let's try one more.

Prediction: carolina_chickadee, Probability: 100.000%

That's pretty amazing. I was surprised at how effective this was even with such low quality photos. I expected that we would at least see lower probabilities even if the model gets them right, but it's quite certain. That's the power of good, clean data combined with the latest pre-trained vision architectures!